Montessori math education is rooted in concrete experience with physical materials to help children's self-discovery of abstract mathematical concepts.

What do you remember about learning math? Many adults remember math being frustrating or tricky to understand, and this feeling often lasts into adulthood. But math is central to everyday life and essential to understanding the world. So where is the disconnect? One underlying problem may be how math is traditionally introduced to children. Math education often teaches abstract concepts before children fully understand the foundations and underlying principles.

In Montessori math, education is based on concrete materials rather than abstract concepts. The child manipulates physical materials that guide them to their own abstraction of complicated mathematical concepts. The materials are intentionally and scientifically designed to be presented sequentially to help children move through levels of math understanding. Children are encouraged to make discoveries through exploring the materials, which is how they begin to understand the rules and formulas of math. The role of the teacher, or guide, is to keep the child interested in making their own discoveries. This process of discovery and understanding is individual to each child.

Similar to how children’s minds are ready to receive and learn language from birth, they are also primed with a mathematical mind. This is not something conscious, but rather a child’s ability to think in mathematical terms from an early age. In Montessori education, children begin formal math work at age four to ensure they are intellectually ready to enjoy the math exercise. By utilizing concrete objects that a child can interact with, manipulate, and observe, Montessori math education works

with a child's innate mathematical mind to give them a solid foundation in math understanding. However, if this mathematical mind is not developed concretely, children may not be able to achieve their math potential. It may become too frustrating to understand abstract mathematical concepts and the feeling of failure leads children to decide math is not for them. The same is true if formal math education is introduced too early, or before age four.

Before age four, children’s practical life experiences help prepare them for their future math learning. There are also ways to support this early math learning at home. Using math language with young children in an informal way, like “We are leaving in two minutes” and “How many plates will we need at the table for dinner?” helps to put mathematical thinking into simple terms. Caregivers can also encourage children to explore the mathematical aspects of their home environment, like temperature, quantity, size, order, and time. Baking and playing cards are two ways to directly engage young children in mathematical thinking before the age of formal math lessons.

Here are a few examples of Montessori math materials:

Number Rods

The first concrete math material the child works with is called the

Number Rods. While most children can count well beyond 10 at age 4, the Number Rods are critical for learning one-to-one correspondence and having a concrete experience with quantity before introducing the symbol, in this case, the corresponding numeral.

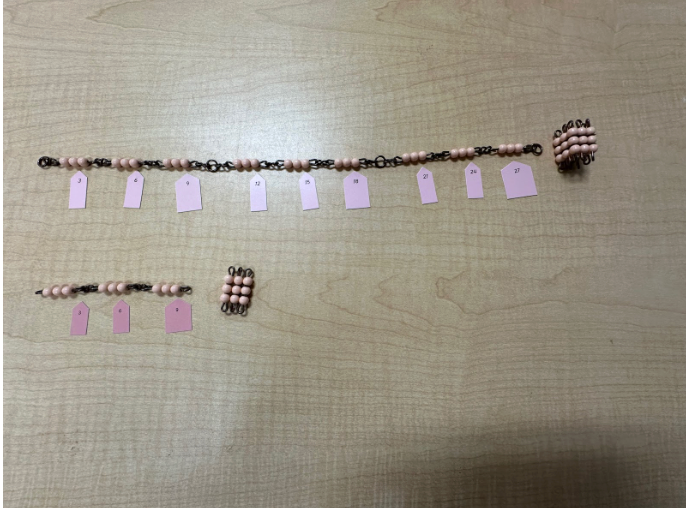

Beads and Bead Chains

When the child has a very good understanding of the numbers 1-10, we move on to working with larger numbers using beads. Pictured is unit (1), 10, 100, and 1000 with their corresponding cards. Using these beads and a series of games, the child is introduced to numbers in the teens, hundreds, and thousands.

The child uses the

short and long bead chains to master counting 1-1000 and to learn skip counting, a preparation for multiplication. There are many activities that can be done with the chains.

Pictured below is the

3-chain. The shorter chain represents the square of 3, which is 9, and the longer chain represents the cube of 3, which is 27. These concrete experiences lead to a deep understanding of math and the relationship between numbers. It is very exciting to lay out and count the longest 1000 chain!

“A much more real danger, and alas one that is present in many schools, is that of hustling on the child’s mind, and forcing it to do sums in the abstract before it has formed a clear notion of the operation in the concrete”

-Dr. Maria Montessori